Medieval Effigy Found Hidden Beneath English Church’s Pipe Organ

The newly restored carving is the oldest alabaster effigy of a priest discovered in the U.K. to date

:focal(525x278:526x279)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/7b/e67b4e83-e1ea-4672-8342-fba949c9137b/effigy.jpg)

Four years ago, Derbyshire resident Anne Heathcote received an unexpected phone call from the Church Monuments Society, a London-based group dedicated to celebrating, studying and conserving tomb carvings both in the United Kingdom and further afield.

As Heathcote tells the Observer’s Donna Ferguson, the society contacted her in hopes of learning more about a statue housed at St. Wilfrid’s, the tenth-century church where she serves as warden.

“They said, ‘We know from a Victorian book that recorded monuments in churches, that you’ve got an effigy of a priest in there,’” she recalls.

After confirming the record’s accuracy, Heathcote sent the society a photograph of the work, which had spent centuries hidden beneath the church’s pipe organ.

“It was filthy, but I immediately got an email pinged back, full of excitement, saying, ‘This looks like a very important effigy,’” the warden adds. “I was dumbfounded.”

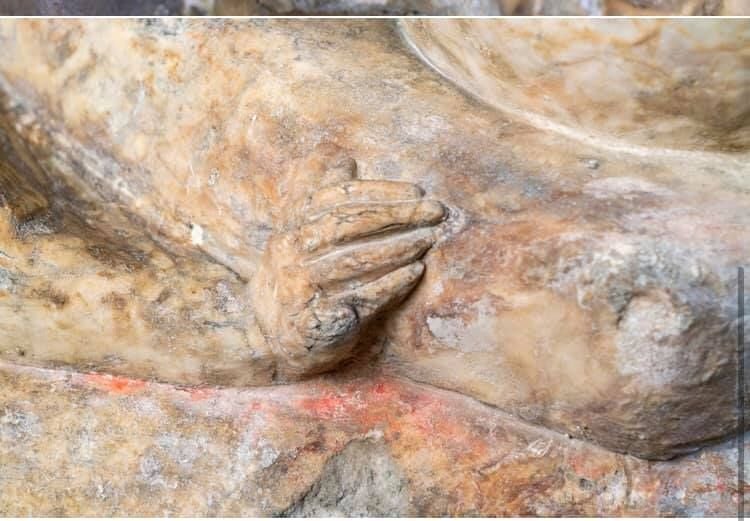

Some 670 years after the sculpture’s creation, experts are hailing it as “exciting beyond our expectations,” reports Lynette Pinchess for Derbyshire Live. Removed from its hiding place as part of renovations aimed at transforming St. Wilfrid’s into a community center, the 3,360-pound statue is the oldest alabaster effigy of a priest found in the U.K. to date. It boasts more remnants of medieval paint than any other effigy from the era, in addition to rare traces of gold, cinnabar and azurite.

Dated to around 1350, the effigy—which features angels framing its subject’s head and a dog resting at his feet—likely depicts John de Belton, a local priest who died of the Black Death. Though these kinds of ornate memorials became more common during the late 14th century, just six or seven were created during de Belton’s lifetime—a fact that makes his effigy “something of a trendsetter,” as conservation expert David Carrington tells BBC News.

“He would have been a very bright, blingy type of statue when he was first made—so far, the conservators have found dark red, bright blue, black and green paint as well as gold,” says Heathcote to the Observer. “He is wearing priest’s robes, which have been very finely sculpted by someone who was obviously a master sculptor.”

The 14th-century effigy was one of many religious symbols targeted during the English Reformation, which found Henry VIII breaking from the Catholic Church in order to marry Anne Boleyn. Aided by advisor Thomas Cromwell, the Tudor king spent the late 1530s and ’40s shutting down houses of worship, seizing their land and wealth, and engaging in iconoclastic destruction. In doing so, he both eliminated symbols of the papacy and filled his dwindling coffers with funds from the Church’s treasures.

Writing in the 2017 book Heretics and Believers: A History of the Protestant Reformation, historian Peter Marshall recounts an incident in which workers carelessly removed an enormous crucifix from St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. The religious icon came crashing down, killing two hapless laborers.

“The papish priests said it was the will of God for pulling down of the said idols,” a contemporary chronicler noted disdainfully.

At St. Wilfrid’s, Tudor soldiers smashed the effigy’s alabaster face, severed its stone hands and decapitated its protective angels.

“Although his face has certainly been damaged, … it is still possible to see the beauty and skill of the sculptor,” Heathcote tells Derbyshire Live.

Per the Observer, Heathcote raised £10,000 (around $13,500 USD) to clean, analyze and restore the statue. She was ready to unveil it to the public this week but was unable to due to new Covid-19 restrictions. When the church–turned–community center finally opens, the restored carving will go on view in a protective glass case.

Given that de Belton likely succumbed to the Black Death, Heathcote tells the Observer that it’s “very ironic that we’ve put him back there in full view, as good as we can get him, in the same year we’ve got another pandemic.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)