SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE & CULTURAL HERITAGE

How Barbara Dane Carries a Proud Tradition of Singing Truth to Power

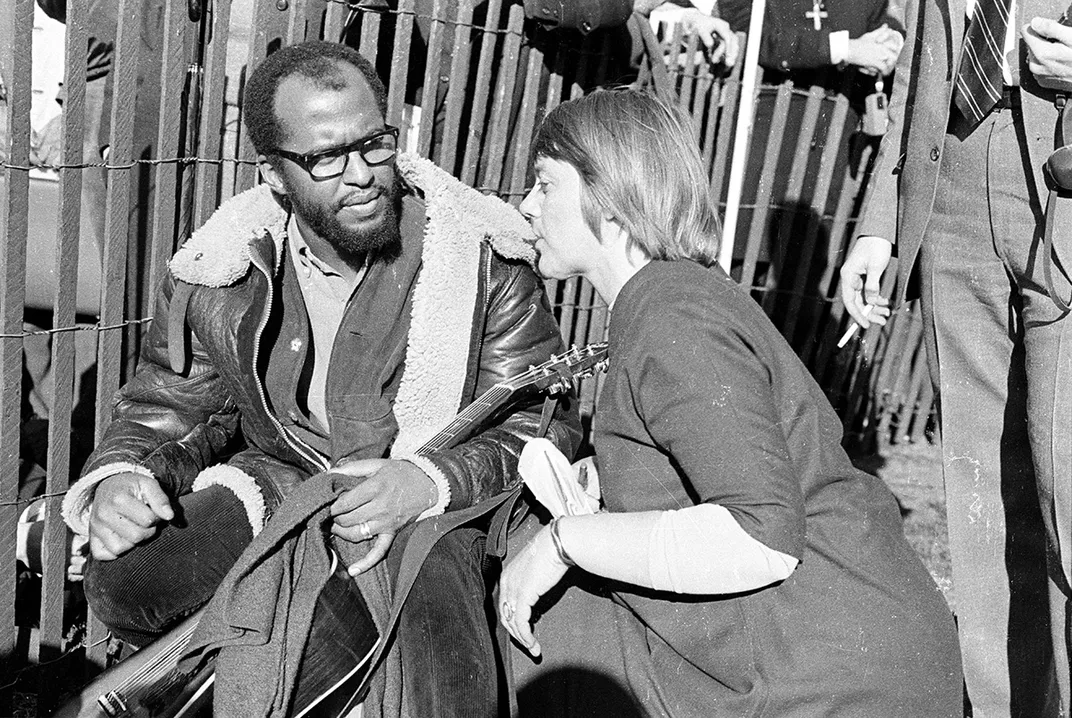

Barbara Dane’s protest music took her to Mississippi Freedom Schools, free speech rallies at UC Berkeley, and in the coffeehouses where active-duty men and women steered clear of military police and regulations forbidding protests on bases.

:focal(600x399:601x400)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/FP-DAVI-BWNE-0160-35_1.jpg)

There are times when a songwriter, a song, and a moment come together to make an impact beyond anyone’s expectations. That’s precisely what happened when Los Angeles-based songwriter Connie Kim (on stage, she’s MILCK) performed “Quiet” during the Women’s March in Washington, D.C, on January 21, 2017.

Originally written a year before the march with Adrian Gonzalez to address Kim’s personal trauma from an abusive relationship, they turned pain into power: “I can’t keep quiet / A one-woman riot.” A year later, the song served a wider purpose and a much larger audience.

Starting with smaller groups of women singing a cappella in different locations throughout the country, and without the benefit of in-person, live rehearsals, Kim found herself on the National Mall. She’s heard of choirs in Ghana, Sweden, Australia, Philadelphia, New York City, and Los Angeles singing “Quiet.” Her “one-woman riot” grew to millions: “Let it out now / There’ll be someone who understands.”

Kim concedes, “It’s not my song. It’s our song.”

Today on International Women’s Day, it’s time to connect the newest generation of songwriters like MILCK to a long and proud tradition of singing truth to power.

Since the 2016 presidential election, millions of people have found themselves in the streets, holding signs, chanting, singing, occasionally braving inclement weather, and probably meeting others they never expected to know. “I never thought I’d be out here, for hours,” many have said, some taking to protest for the first time in their lives. Maybe it was what was said on the campaign trail, how it was said, or simply who was saying it. For all the first-timers out there, no matter how they feel about the politics of the day, people finding connection in the streets should know that singer-agitator Barbara Dane has been connecting audiences and marchers for years, decades even.

As a teen, Dane sang for striking autoworkers in her hometown of Detroit. She attended the Prague Youth Festival in 1947 and connected local protest with stories of young people from around the world. With a natural gift for swinging and singing the blues, she launched a career in jazz that caught the attention of some of the greatest on the scene, like Louis Armstrong. By the end of the 1950s, Dane was featured in Ebony magazine, the first white woman to be featured in those pages and photographed with blues greats.

Forget about the sublime images of suburban life on TV from the 1950s. The postwar years saw millions taking up the banner of decolonization and national liberation. Americans couldn’t ignore those tides and neither could Barbara Dane. Her protest music took her to Mississippi Freedom Schools, free speech rallies at UC Berkeley, and in the coffeehouses where active-duty men and women steered clear of military police and regulations forbidding protests on bases. Dane was seemingly everywhere, leading chants, reinterpreting songs by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Sara Ogan Gunning.

By the late 1960s, Dane took up an invitation to visit Cuba, where she was greeted warmly. Did she care about the U.S. State Department’s admonition against making the visit? Her response was sharp and clear: “We’re a country that promotes freedom, so why can’t this free person go where she wants to go?”

It’s no accident that Dane found kindred spirits among the ranks of singers and songwriters working in the nueva canción genre. This was a popular music that celebrated a constellation of impulses and influences, ranging from local, indigenous, folk, and ethnic instrumentation, stylizing, and vocalizing, to lyrics that were political, socially aware, defiant, or even comedic at times. Her Havana trip not only gave her a strong anchor in nueva canción for reference, but she also found singer-songwriters from Europe and Asia who shared those passions and interests.

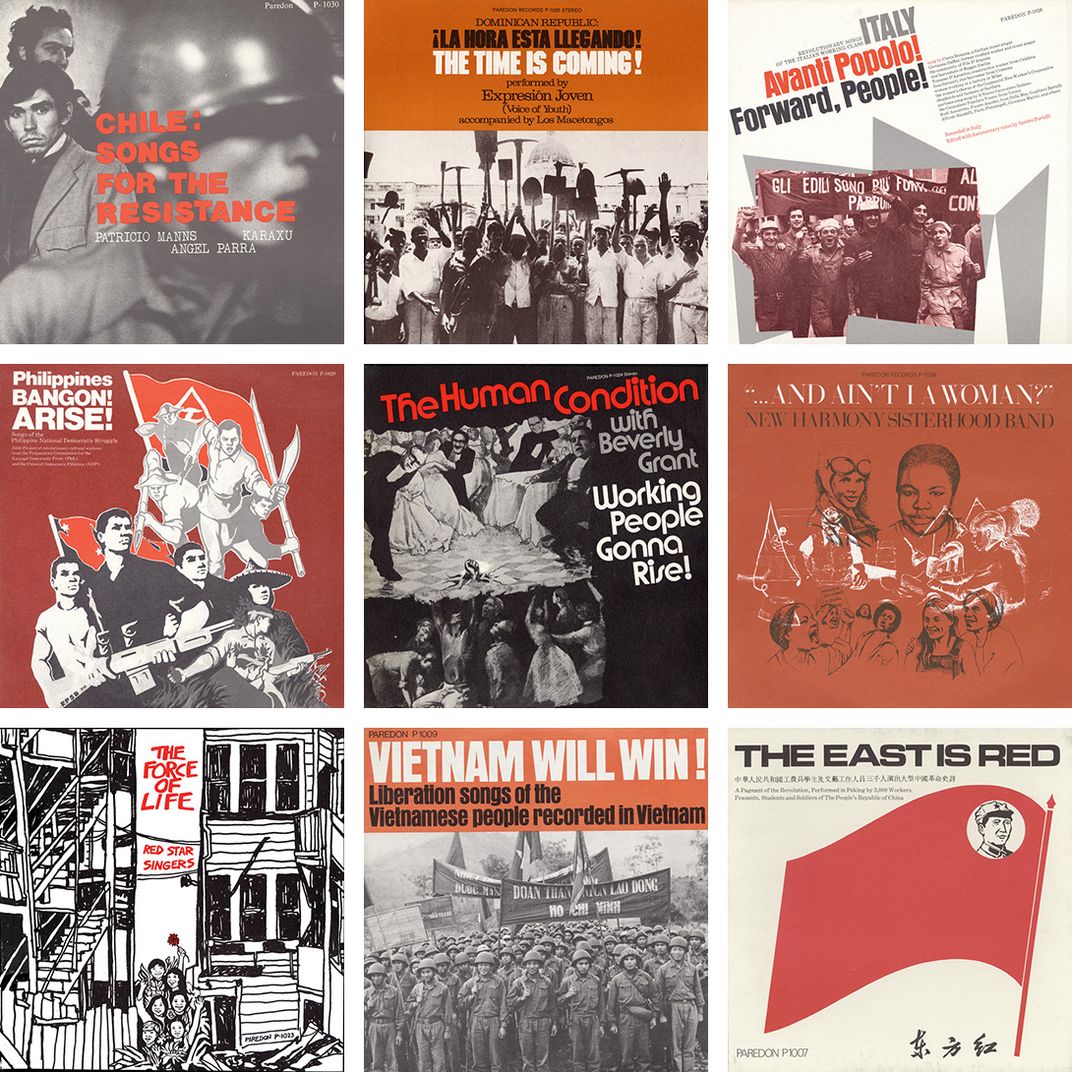

These connections formed the basis of Paredon Records, the recording label she founded with Irwin Silber, a skilled critic and record producer. From 1970 to 1985, Dane and Silber released fifty albums that documented protest music from around the world. The musical messages reflected the stakes and the hopeful dreams of millions trying to make sense of a world dominated by superpowers with world-ending weaponry.

The songs and the writers came from every corner: students from Thailand and the Dominican Republic. Activists from Chile. Mass-party workers from the Philippines and Italy. Working-class rock by Brooklynite Bev Grant, anti-imperialist folk by Berkeley’s Red Star Singers, and anti-patriarchal songs by the New Harmony Sisterhood Band. But don’t think you can reduce Dane’s Paredon collection to merely strident messaging.

Throughout the catalog, you feel Dane’s attention to what it can mean to link the songwriter, the song, and the moment into something soulful and personal. Many of the musicians featured on Paredon trusted Dane because she was also an experienced singer in addition to being the label’s co-founder, writer of dozens of liner notes, and producer. She had the practical experience of knowing life as a working musician in an industry and in social movements dominated by men. She more than held her own. Audiences trusted her politics and attitude. And fellow musicians heard in Dane’s voice the hard life of singing for your living.

Getting out on the road and performing kept her vital and engaged. For Dane, as she explained in the liner notes to Barbara Dane Sings the Blues, the road taught her

what it means to be alive, to value life above anything and rage like a tiger to keep it... to spend it with care instead of trading it for a new car or a fur coat... to treasure the moments that are real between human beings without counting the cost or trying to bargain, because there’s no price on that beauty. The only thing we have, really, is our time alive, and I don’t think they’ve printed enough to buy mine. How about yours?

It’s not too late for MILCK to meet up with Dane. I had the chance to catch Dane’s eighty-fifth birthday concert, where she sold out the Freight and Salvage in Berkeley, California. For the first set, her quintet backed her as she delivered a slate of jazz and blues standards. After the intermission, members of her family performed—her daughter, Nina, singing flamenco; her two sons, Jesse and Pablo, and her grandson on guitar. Toward the very end of the evening, she brought up her entire family, spanning four generations, and had her great-granddaughter step up to the mic to sing.

It was getting late into the evening, and I was going to miss my train back into the city. I left just as Dane led the crowd through chorus after rousing chorus of “We Shall Not Be Moved.” I could hear her strong voice fade as I hit the street and descended into the subway station.

I hope MILCK gets a chance to see Dane, now ninety, perform live. Or maybe they could teach each other their favorite songs. Both of them, so much more than a one-woman riot.

Above, watch Barbara Dane sing and share stories during the 2020 Smithsonian Folklife Festival’s Sisterfire SongTalk.

Find the two-disc retrospective of Barbara Dane’s recordings, Hot Jazz, Cool Blues & Hard-Hitting Songs, and a vinyl reissue of Barbara Dane and the Chambers Brothers for sale from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. You can also explore the history, messages, and art of Paredon Records in a new online exhibition.

Theodore S. Gonzalves is curator of Asian Pacific American history at Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. He is currently writing a cultural history of Paredon Records.