The Schoolteacher Who Saved Her Students From the Nazis

A new book explores the life of Anna Essinger, who led an entire school’s daring escape from Germany in 1933

:focal(973x1029:974x1030)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/03/c303f413-7ad9-4987-914c-6e628d6b728d/anna.jpg)

It took Anna Essinger six months of planning to devise the remarkable secret escape of her entire school from Nazi Germany. On the critical day, October 5, 1933, the 54-year-old headmistress’ most trusted staff members spread out in a network of three teams across Germany. Parents and children quietly made their way to preassigned railway stations along the three key rail routes out of the country. Martin Schwarz, the school’s teacher of religious affairs, was to lead one group, discreetly picking up a child at each station along the Rhine River from Basel. Anna’s sister, the school nurse, Paula Essinger, set out from Munich to Herrlingen and on to Stuttgart and Mannheim, also collecting pupils on the way. Hanna Bergas, who taught English, French and art history, led the final group across northern Germany.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dc/28/dc28e74c-66f6-426a-80f8-97de4dd142a4/anna_essinger.jpeg)

Everyone knew the dangers. “Obviously mass emigration was prohibited,” Paula wrote later. “We had to avoid all suspicion.” But the complex plot involved large numbers of people—parents, staff and children. If even one person talked, it was hard to know what might happen. Would the thuggish Brown Shirts storm the trains? Would a child accidentally give the game away? It was even possible the Gestapo had already pieced together Anna’s plan and would stop everybody at the border. At concentration camps and prisons across Germany, the Nazis already held thousands of political prisoners and others they deemed insufficiently supportive of the regime without charge or recourse.

In her memoirs, Bergas recalls arriving at Station Zoologischer Garten in Berlin, where ten boys and girls were waiting—a large and not inconspicuous group. As agreed in advance, only a few parents came to say goodbye. Although each child had packed enough for two years, everything had to appear normal, as though this was just an ordinary school trip. “It was a quiet subdued leave-taking,” Bergas wrote. “Much thought and talk had been spent on this moment in previous weeks and now everybody was controlled.” Her own elderly mother was also on the platform; Bergas felt the wrench keenly, wondering if and when they would meet again.

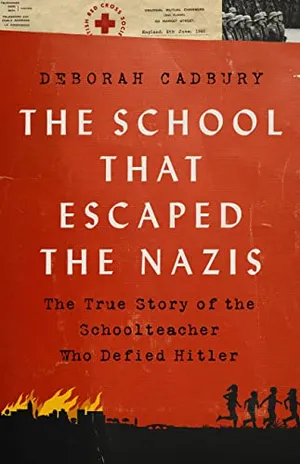

But like the other teachers, Bergas put her complete trust in “Tante” or Aunt Anna, as she was known to her students, who had founded the school and conceived the plan to save it from the grip of the Nazis. Only recently has Anna’s far-sighted, courageous and principled stand against the Nazis gained broader recognition beyond the circle of those whose lives she touched. As I describe in my new book, The School That Escaped the Nazis, her role in saving and educating hundreds of children is a powerful example of one woman’s refusal to let her belief in an equitable and more compassionate world succumb to violent hatred and political extremism.

The School That Escaped the Nazis: The True Story of the Schoolteacher Who Defied Hitler

The extraordinary true story of a courageous school principal who saw the dangers of Nazi Germany and took drastic steps to save those in harm’s way

Born to a secular German Jewish family in Ulm, in southern Germany, tall, red-haired Anna was the oldest of nine children, and she grew up accustomed to helping her mother care for her brothers and sisters. Unusually for a young woman in the early 20th century, Anna self-funded her education abroad, earning both an undergraduate degree and a Master’s degree in education from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Anna was inspired by America’s democratic freedoms and education system, which she came to believe was crucial to progress and the healthy functioning of a free society.

After nearly 20 years in America, she returned to Germany after the First World War, and in 1926 she opened a school of her own. Landschulheim Herrlingen, located near Ulm, did away with the traditional German approach to education, which was based on strict discipline and harsh punishments. Instead, the progressive, non-denominational boarding school put each child at the center of his or her education, encouraging their natural curiosity and creativity. Anna often quoted the English writer and philosopher John Ruskin: “The entire object of true education is to make people not merely industrious, but to love industry, not merely learned, but to love knowledge, not merely pure, but to love purity, not merely just, but to hunger and thirst after justice.” As much emphasis was placed on learning practical skills as on academic achievement, and children contributed to the community as they might at home, tending the garden, cooking, cleaning.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7c/0e/7c0e90b3-daf5-47b5-8c1b-f29a6b83fb31/fullsizeoutput_10bd1.jpeg)

According to former students, the atmosphere Anna created was unique. “For me, Herrlingen meant freedom,” recalled Wolfgang Leonhard. “We learned what we really wanted to learn.” Susanne Trachsler reflected that the school nurtured “intellectual curiosity, authority without violence, respect and solidarity, the courage to think for yourself, sport, foreign languages, to climb trees”—and, perhaps most important, “joie de vivre.” Another student, Ruth Sohar, said, “We learned to get along with each other. Every religion, every race, all kinds of people. We were like a big family.’

But with Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, Anna began to fear that her life’s work was in jeopardy. She had read Mein Kampf, and she foresaw that Hitler would plunge Germany into an abyss where there was no place for freedom of thought or expression—or perhaps even for survival itself. In January 1933, Germany’s aging president appointed Hitler chancellor; in March, the “Enabling Act” transformed him into Germany’s all-powerful dictator. Within days, Anna was ordered to fly a swastika over the school at Herrlingen. Outraged, she staged a one-woman protest. She hastily organized a three-day camping trip for her students, and only when no one was left in the school did she raise the Nazi flag.

The swastika flying over Herrlingen was like a beacon that showed Anna the impossibility of a future for herself or her students in Hitler’s Germany. “I felt that Germany was no longer a place in which to bring up children in honesty and freedom,” she later reflected. The Nazis appealed to the worst in human nature, and they tolerated no dissent. Anna, by contrast, believed in freedom—freedom of spirit, freedom to think, to question, to challenge, to live without fear. Under Hitler, lies were being turned into the truth; black was being turned into white. How could she teach future generations if she couldn’t speak the truth without fear? She knew she must act. Somehow, she had to smuggle her school to safety.

At night, she plotted with trusted staff members about how to escape. If the Nazis learned that she planned to relocate the school and its entire student body, they might impose crippling financial sanctions or seize the school and requisition it for the Hitler Youth. If the press got hold of the story, it could cause a sensation. Everything hung in the balance. Already Anna had heard that Kurt Hahn, the famous German Jewish educator and founder of the acclaimed Salem School in Baden-Wurttemberg, had been arrested.

“For me, Herrlingen meant freedom. We learned what we really wanted to learn.”

By late spring 1933, Anna was traveling across Europe, quietly searching for a new site in Switzerland, Sweden or Denmark. In June, she sought help in Britain, where she found a favorable reception in Jewish and Quaker circles. She was soon introduced to backers who agreed to help her secretly raise funds and find her school a suitable new home.

Anna returned home to ominous developments. On July 15, 1933, in Ulm Minster square, the Nazis organized a huge bonfire of books by Jewish scholars—Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx. Despite growing risks, Anna pressed ahead, arranging small, secret gatherings across Germany for the school’s parents to discuss their future. The response to Anna’s plan was overwhelming. Nearly all of the Jewish parents, as well as many non-Jewish families, entrusted their children to Anna. With the scheme now in motion, Anna’s staff spent the summer secretly teaching the students English and offering lessons in the history and culture of England.

In early September, as Anna and her staff were finalizing their plans, another Nazi rally was held in Ulm, and a crowd surged into the church square to hear Hitler speak. The local papers uniformly celebrated the event. The next day, Hitler visited nearby military battalions, and his convoy passed directly through the village of Herrlingen, not far from Anna’s school, unaware of the small rebellion coalescing a short distance away.

Two weeks after Hitler’s rally, in late September 1933, Anna and an advance party of 12 teachers and senior pupils set out for England. By their very actions, they revealed their opposition to the Nazi regime. Innocent politicians, Jews and dissenting Christian clergy languished in concentration camps for just such alleged crimes. How would Anna’s own cover story of a short sabbatical abroad stand up before the Gestapo if it became clear an entire school would follow her? Anna’s eyes scanned each station for any sign of trouble, but she had put months into preparing for this day, and the journey passed without incident.

Ten days later, on October 5, the three remaining groups set out across Germany as though on an ordinary school outing. The tension was palpable on the train carrying Bergas and her group as they made their way west to the border. At the border station, they heard shouted instructions and saw armed Nazi guards on the platform. Their papers were inspected. Finally, the whistle blew, and the train moved forward, gathering speed. The children didn’t relax until they reached Luxembourg.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a3/b1/a3b181e6-8ff5-4f7e-a11b-78bf982d6d47/fullsizeoutput_10bf2.jpeg)

At the docks at Ostend, Belgium, they caught sight of Paula and another contingent of classmates. Soon the third group arrived. Now together, the 65 children traveled on with their teachers. When they approached the famous white cliffs of Dover, there on the quay side was Tante Anna, waiting to escort her pupils on the final leg of the journey.

Three red buses wound their way through the Kent countryside before stopping before a gracious manor house, which would soon become known as the Bunce Court School, named for its historic buildings. It was clear by the whoops and screams of delight from the children that they knew they were safe.

But this was just the beginning. After the first group of children from Germany came hundreds more, traumatized by the ever-escalating catastrophe on the continent. In time, child refugees arrived from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland, as their parents became increasingly desperate and used whatever funds and other means left available to them to send their children abroad. In the months before the war, a large group of at least 50 children arrived via Kindertransport. After the war came those who had survived ghettos, labor camps and concentration camps or lived in hiding. Many were now orphaned or had no knowledge of what became of their families.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c1/71/c17190d9-ba12-4cb1-b9d2-c10828fabfe5/bunce-court-exterior-of-side.jpeg)

Although little was known about dealing with extreme trauma in the 1930s and ’40s, at Bunce Court Anna sought to create a home where children could not only recover but be inspired. These were innocents who had fought against all odds for a chance to live. She tried to show her pupils a path that would lead them away from pain and hatred toward healing and love. As at Herrlingen, a nurturing sense of community allowed the children to feel loved and supported. Especially important was the emphasis Anna placed on everybody contributing, as though part of a large family, which returned to the children a sense of their value and self-worth. In addition to their studies, they helped to grow the vegetables they ate, they looked after animals, they cleaned and cooked. The children responded to this feeling of belonging. For many orphaned survivors, their classmates became like new siblings and the teachers like parents.

Anna Rose, originally from Poland, survived the war by hiding in a single room for three years. She recalled her first spring at Bunce Court, saying, “I saw snow melting and crocuses and snowdrops and thought it was so beautiful I was mesmerized. I no longer had to fear ambush or murder.” Eventually, “Enveloped in this totally engaging, affectionate environment,” she thought, ‘This is what home is like.’”

Sam Oliner, also from Poland, arrived from a displaced persons camp in 1945 “totally uneducated and forlorn.” The staff observed his intuitive skill with animals, and they encouraged him to keep pets of his own. He learned “not only reading and writing but also how to cooperate, how to be kind,” he said. Tante Anna in particular struck him as “a farsighted and truly altruistic human being.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2b/b9/2bb98404-164e-45b3-b230-1be38d55ad07/arthur_and_anna_leaving_poland_1946.jpg)

By 1948, with Anna’s health declining, the school searched for a suitable replacement, but when one couldn’t be found, the Bunce Court School reluctantly closed its doors. Anna herself, by now almost blind, retired to the isolation hut at Bunce Court. For years she received letters from former students, who numbered more than 900 and had gone on to live all over the world. Many came to visit the woman they felt had saved them, and they would read to her when her sight finally failed.

Anna died in 1960, having lived long enough to launch the careers of many of the school’s children, but not long enough to see them achieve their greatest successes. Anna Rose, for instance, eventually settled in California and was elected city auditor in Berkeley. Oliner became a professor at Humboldt State University, also in California, where he founded the Altruistic Behavior Institute, specializing in the study of tolerance and altruism. Anna’s school “enabled us to recuperate emotionally from our wartime experiences,” he said. “The people of Bunce Court showed us love.”

This essay is based on The School That Escaped the Nazis: The True Story of the Schoolteacher Who Defied Hitler by Deborah Cadbury. Published by PublicAffairs Books.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.